The Quiet Tool I Almost Forgot I Had #040

Unlearning analysis to rediscover intuition—and why it might matter more than we think.

This week I thought I was learning something new about myself—or maybe unlearning something—only to realize I was tapping back into something that had always been there.

If you’ve read the last couple of newsletters, you know it’s been a full season of day-to-day stories. Lately, I’ve been surprisingly social—even for me.

Travel, weddings, dinners, birthdays, hangouts, concerts, breakfasts… you name it.

My social battery? Definitely tested—and somehow, it thrived.

Somewhere in between all of that, I’ve been sharing my project whenever I get the chance. Because I genuinely believe change is possible, even if it’s slow, even if it starts small.

My family—the close ones—have started promoting it too. We’ve talked about it with friends, new faces, old circles. Sometimes, I don’t even have to bring it up. They do.

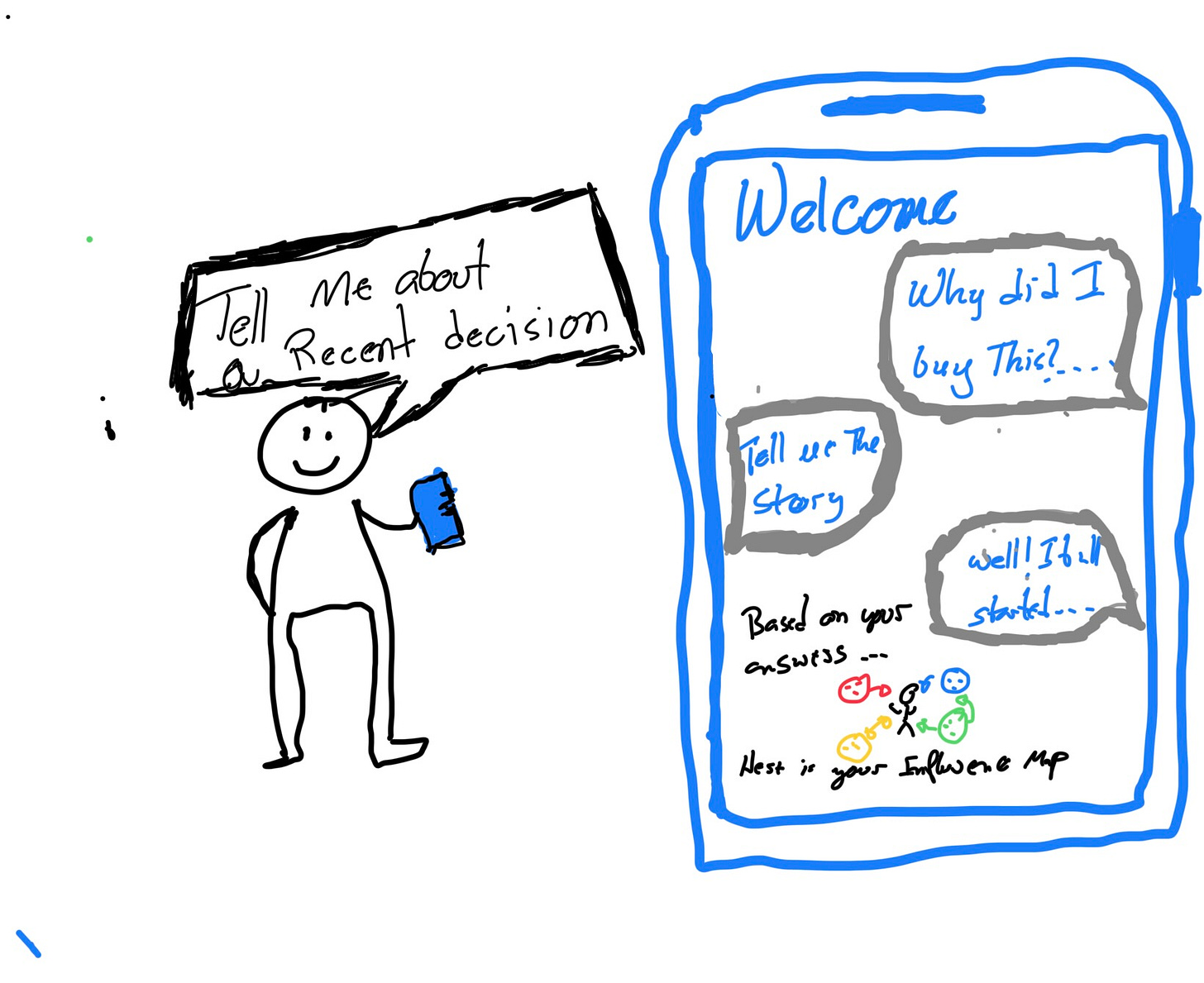

“How might we help our close peers recognize and respond more intentionally to the social influences shaping their everyday decisions?”

The question has sparked some great responses:

“That could help me at work.”

“I’d use that to understand client behavior.”

The feedback has been rich—little comments, quick thoughts—but they all add up. And I’m grateful for every one.

When the Brain Wants to Build

While collecting the feedback, my second nature said… ahh I think I need to start working on solutions, I’m ready. So ready I had selected a code stack to prototype, and another one in case it gave me good results.

I was laying out plans for how to start building it into a real service… I was going to build a BOT, with AI and all.

Check out my super drawing of the prototype!

…and all of a sudden… the course itself takes an unexpected turn!

It doesn’t jump into prototyping… it goes into a parallel way of analyzing.

Or anti-analyzing maybe?

Intuition.

Wait… Intuition?

Have you ever asked yourselves, do you intentionally use intuition in your day to day?

I’ll let that sit for a moment…

What was the first thing that came to mind?

What??? Intuition like, hey I want to submit a report, let’s see what my intuition says?

Well, I had never asked myself if I use intuition. I wasn’t even aware of the possibility of “using” it—of harnessing it, taking advantage of it, or thinking of it as a tool that could actually drive change.

Even though I’ve read about it. Books of all kinds, some I’ve even cited here in SiMPL. Still, I couldn’t recall a moment when I had been exposed to that idea firsthand—that maybe I had been using intuition all along, but never called it that.

Intentionally, maybe. But aware of it? Not really.

Unlearning, One Layer at a Time

So, this week I’ll share my learnings, self-discoveries, and see if I can help you unlearn a thing or two along the way.

And for those of you thinking… this is bullcrap, don’t tell me you fell for that hippie sht!*—yeah, I hear you.

This is just a different approach.

Getting from questioning to unlearning takes a while. But I’m used to that. And before jumping into the full story, let me share part of the feedback I wrote at the end of that chapter to the teaching staff. Here’s an abstract:

“I really loved this lesson. It’s the first time in my life that I’ve paused to question the intentionality of intuition in my day-to-day. Surprisingly, by measuring it, I realized that I do use intuition—despite leaning heavily toward the rational side of things.

I can tell when my sourdough is perfectly proofed without a timer… when something in the oven is just about ready… when to slide into a note while jamming on the guitar… or even when to call a friend or family member—sometimes getting it right, and sometimes learning from getting it wrong.

But treating intuition as a tool I can name, use, and refine? That’s new for me—and it’s powerful. Thank you for that.”

Take that as my own testimony—there’s something here worth exploring.

The Coin Trick and the Missing Tool

To understand what we’re really talking about, let’s define the ground we’re standing on.

First, I’m sharing this with the excitement of a kid who just discovered an old trick. One of those things that feels brand new even if it’s been around forever.

You ever show a kid a simple coin trick? The look on their face is gold. They try over and over to figure it out. The last thing they imagine is deception. They want to believe it’s magic.

And what’s the usual follow-up?

“Can you teach me?”

A couple of years ago, during the year-end holidays, we were having dinner. My in-laws were visiting, and Rafael—my father-in-law—asked Axel to get him a coin. He proceeded, with the flair of a magician, to set the whole scene: sound effects, hand claps, building tension… and then—puff—the coin disappeared.

Axel was astonished.

They repeated the trick at least ten times, and he could never figure it out.

Eventually, Rafael decided to teach him. He explained the trick, how to perform it, where to hide the coin. The magic seemed to disappear—but not the eagerness. Axel wanted to be a magician.

The one thing he didn’t notice—and I mean, he’s a kid—is that 90% of the trick is in the performance. Not the coin. It’s the sounds, the tone, the movement. It’s how you manipulate the audience just enough for them to lose track of where the coin went.

That moment came to mind when I read Roger Martin’s quote in the course. It hit me. It was an abstraction I’d seen before—but this time it landed.

And me being me… I grabbed the book. One I’d read back when I was deep in my Design Thinking phase, reading everything I could get my hands on: The Design of Business: Why Design Thinking Is the Next Competitive Advantage.

I skimmed through it until I found the quote.

“If your only tools are deduction and induction, you are not equipped to deal with the mysteries of the future. You are simply extrapolating from the past. To create new ideas, you need abductive reasoning.”

—Roger Martin

It’s not easy to interpret this at first glance, so let’s break it down.

Roger walks through what each of these terms means.

Deduction is applying general rules to specific cases. Logic, math. Sherlock Holmes stuff. (Big fan!)

Induction is inferring general rules from specific cases. Data patterns. Analytics. Like when you watch three Marvel movies in a row, and assume every superhero is going to have daddy issues.

And then comes abduction—the missing piece. The one that lets you imagine what might be true to explain an observation. It’s the birthplace of creative hypotheses. And the core of design thinking.

Defining My Own Intuition

Then, I was asked—as part of one of the lesson deliverables—to write my own definition of intuition. And you know I like having my own definitions.

This was mine:

That inner wisdom that uses conscious and unconscious knowledge to make split-second decisions.

Up to that point, I hadn’t realized just how much of my life I’d spent getting to that definition.

There’s definitely a lot of Daniel Kahneman in there. Thinking, Fast and Slow kind of stuff. But there was something else too.

The deeper we got into the course, the more questions we were asked, the more it started to click.

Hey—I even made a drawing of my intuition.

One of the prompts asked us to describe a time we’d used one of these techniques. I started writing—and realized I already had a habit. A small thing, but a clear one.

When I used to go into the office, I’d walk to the coffee shop—not really for the coffee, but to unwind. To walk. To reset. Whether I went alone or with a colleague, it didn’t matter. Just getting up and walking to the machine or the street helped me find whatever I was looking for.

And I still do it. From my home office, I step outside to let the dog out, open the fridge, cook something if I can. That little pause still resets me more often than not.

And while I was writing that down, it hit me—yes. I had used intuition before. Intentionally.

The Startup Shrink

I knew it. The first hint had come after one of the lessons where they guided us—almost like a meditation—into exploring how we connect with intuition.

I was in familiar territory.

It was 2013. I was in Silicon Valley, post-corporate, fully bitten by the startup bug. I had dropped everything to chase the dream: build an app, make it big, change the game, get rich—or at least get funded.

To help cover costs, we ran a side business doing web development. I was in charge of making that part of the operation work—keeping developers paid, covering the office, paying bills. If you think an app builds itself, well… back in 2013, it didn’t.

One of our clients was Dr. Timothy Dukes. I’ll never forget the guy. A sharp, thoughtful psychiatrist who was about to release his book The Present Parent. We did some collaboration with him—team-building stuff, coaching sessions, big-picture thinking.

Did it work out? Not really, not for us as a group. But individually, I learned a lot, and I bet he got some good insights.

I remember going to his place in Sausalito just to talk. No pressure. Just tea and conversation. I didn’t have a car, so I’d get there however I could. Sometimes I’d bring a book and read before or after our chats.

Sausalito had that kind of vibe. That smooth, still kind of quiet that lets you think without interruptions. That lets you go deep. Digest. Observe.

At the time, I had just finished The Lean Startup by Eric Ries. Yes—that guy. The one everyone quotes with Start with Why and the golden circle and all that (don’t worry, we can unpack that another day).

I was looking for something new to read. I had seen the name Alan Watts—either on Timothy’s shelf or in this tiny used bookstore across the street from where I sat.

I thought, hmm… let’s look him up. See if he’s the next one I should dive into.

I found a recording online, plugged in my earphones—Samsung Galaxy S4 in hand—and hit play.

And then… came the story.

The Chinese Farmer (As Told by Alan Watts)

“Once upon a time, there was a Chinese farmer whose horse ran away. That evening, all his neighbors came around to commiserate. They said, ‘We are so sorry to hear your horse has run away. This is most unfortunate.’

The farmer said, ‘Maybe.’

The next day the horse came back, bringing seven wild horses with it. And in the evening everybody came back and said, ‘Oh, isn’t that lucky. What a great turn of events. You now have eight horses!’

The farmer again said, ‘Maybe.’

The following day his son tried to ride one of the untamed horses, was thrown, and broke his leg. The neighbors then said, ‘Oh dear, that’s too bad,’ and the farmer responded, ‘Maybe.’

The next day the military officials came to draft young men into the army. Seeing the son’s leg was broken, they passed him by.

The neighbors congratulated the farmer on how well things had turned out. The farmer said, ‘Maybe.’”

That didn’t sound like a new recording, at all… Back home, after having dinner and playing an hour of the just-released Batman: Arkham Asylum, his words kept meddling in my mind.

I went online and looked for his bio. Who is this Alan Watts?

And there it was…

He lived in Sausalito. Used to host philosophical meetings there—in the same spot where I had just been hanging out—listening to that amazing Taoist story.

You see, Watts loved to talk about the difference between Taoism and Confucianism.

Confucianism is for the people who live within a set of rules—rituals, structures, duty.

Taoism? That’s for the ones who’ve learned to live outside the rules. The ones who’ve figured out how to disconnect.

He was brought up in Asia, studied philosophy there, and then brought his take on Zen and wu wei to the West Coast, where he taught until he passed in the 1980s.

I wasn’t even born yet.

And there I was, unknowingly sitting in the same little walkway by the floating houses that lead to the docks where his boat used to be.

So, Back to Intuition

Watts often retold that ancient Taoist parable to explain the importance of non-judgment, patience, and intuitive acceptance of how life unfolds.

To show how our instinct to label things as “good” or “bad” can blind us to the bigger picture.

Instead, he encouraged people to stay present, observe, and let the situation show you what it really is—before rushing to react.

And in that same spirit, I’ll share a story. One of unlearning.

A Walk Around the Block

Back then, we had an office in San Rafael, CA. In the Chase building on 4th Street. Nice spot—close to restaurants, surrounded by mid-to-small size businesses. The kind of place where you helped others build their digital presence, even while trying to build your own.

We had this really creative brand expert on the team. She had a knack for it—could take a messy idea and give it purpose. She saw things others didn’t. Knew how to work with space, fonts, colors, rhythm.

But yeah—she was kind of a diva.

Thing is, every time there was a client meeting, she’d grab her phone, put on some earphones, and go walking.

Every. Time.

I had a window in my small office, so I could see her go around the block, just talking.

One day I asked, and she said, “Next time we’re both on a call, let’s walk.”

So we did.

And suddenly, things became clearer.

That was her creative method. She couldn’t think in an enclosed space with nerdy developers tapping away at keyboards. She needed to move. To see, smell, eat something random, get a drink—whatever it was, it triggered her thinking.

I think that’s when I learned how to “go for a coffee.”

And I’ve used it ever since.

I’m not creative like her—but I promise, it works.

Is It Still Mumbo Jumbo?

So now, after all this… do you still think it’s mumbo jumbo?

Or could it be something we’ve just learned to forget?

As Alan Watts once said:

“We seldom realize, for example, that our most private thoughts and emotions are not actually our own. For we think in terms of languages and images which we did not invent, but which were given to us by our society.”

We learn through words, writing, diagrams, paintings.

But life is more than that. Intuition fills in the gaps.

Because those things—words, books, slides, prompts—they’re relatively new.

Intuition is old. And wise.

So, tell me—would you try to learn how to harness your intuition?

I’ll leave you with a few questions for introspection.

When was the last time you “just knew” what to do—without needing to explain why?

(Did you listen to it, or second-guess it?)

What small routines help clear your mind and bring unexpected clarity?

(A walk? A shower? Making coffee?)

Have you ever made a decision that didn’t “make sense” on paper—but felt right?

(How did it turn out?)

Do you notice patterns in the moments when your gut gets it right—or wrong?

(What triggers it? What throws it off?)

Do you use your body—movement, dance, exercise—as a way to reset or focus?

(What happens after? Does something shift?)

Thanks for reading. If something in this sparked a memory, a thought, or a story of your own—send it my way. I’d love to hear how intuition plays out in your world.

And if you’re new here:

I write these each week to share what I’m learning, unlearning, and noticing.

If that sounds like something you’d want more of, subscribe to the newsletter.

Very well written my friend, this article really nails why Im good at what I do. Planning and executing a project isn’t just about logic and scientific knowledge, it’s also about trusting your gut. A lot of times, when I’m deep in decision-making, I feel like I can sense something I call ‘the waves of time’ (yeah, sounds a bit silly, I know). It’s like tiny signals that help me pick up on what’s happening around me and see the bigger picture. And funny enough, they usually guide me toward the right path sometimes over the ones that come from critical thinking or PMI books.